As petitioners gather signatures for a possible referendum, attorneys battled over the meaning of words that govern the redistricting process. One big dispute was over how to interpret words that are not in the Missouri Constitution

BY: RUDI KELLER

Missouri Independent

The old cliche that “silence is golden” became “silence is confusing” on Wednesday in Cole County Circuit Court as attorneys argued over the power of Missouri lawmakers to gerrymander congressional maps in the middle of a decade.

Circuit Judge Christopher Limbaugh must decide if language missing from the state Constitution’s directive on when and how to draw congressional district maps means lawmakers were allowed to redraw districts like they did in a September special session.

For those challenging the new map, the omission means lawmakers overstepped their authority.

Chuck Hatfield, an attorney representing the challengers, said drafters of the constitution adopted in 1945 knew what they were doing when they left out the power to revise districts at will.

“We think that language is pretty clear on its face,” Hatfield said.

If the constitutional convention had intended to prevent mid-decade redistricting, the delegates would have included a prohibition, Louis Capozzi, solicitor general in Attorney General Catherine Hanaway’s office, told the judge Wednesday.

Instead, he noted, they didn’t even discuss it.

“The General Assembly has the power to act unless the Missouri Constitution expressly takes a particular power away,” he said.

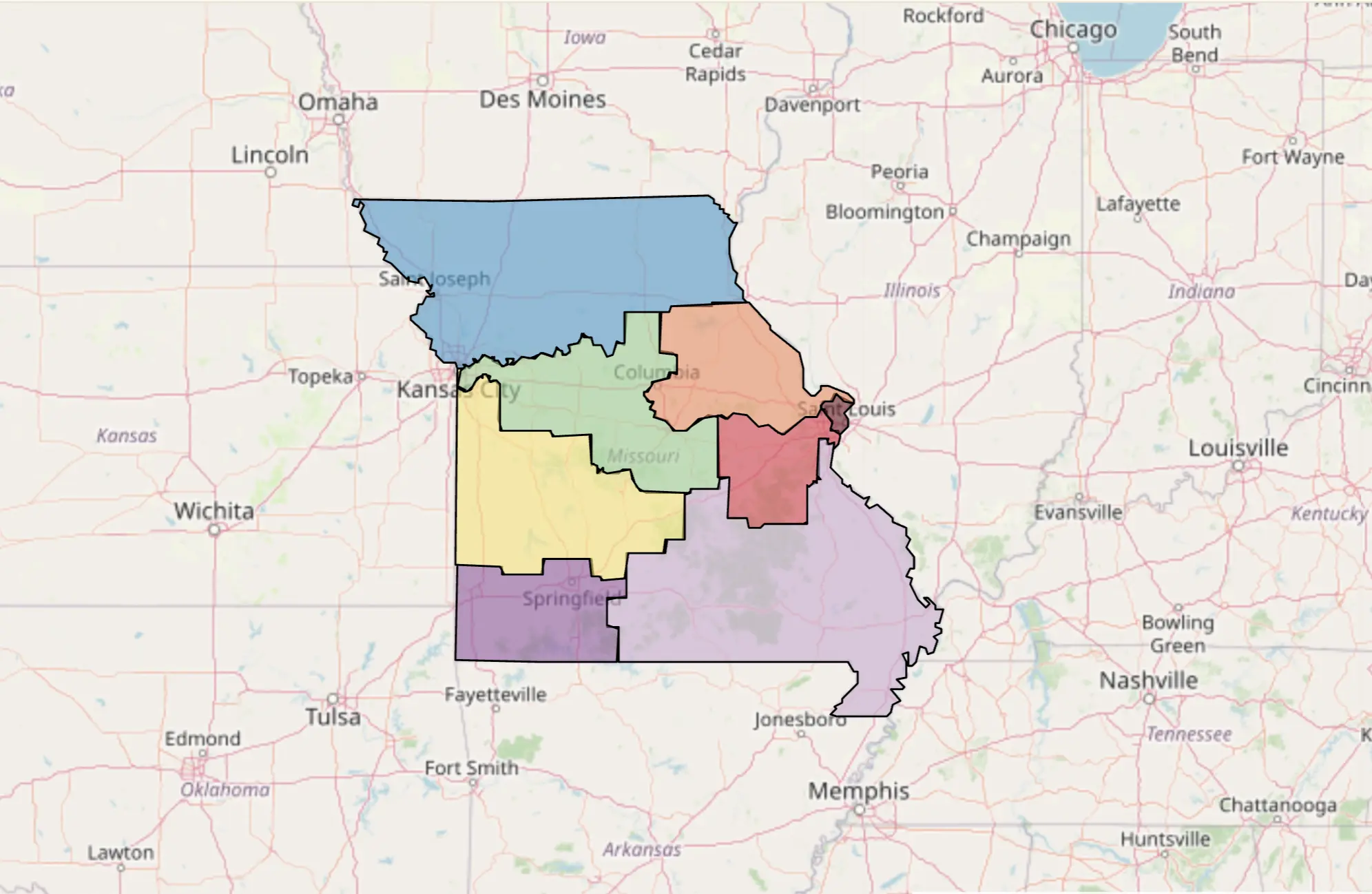

Gov. Mike Kehoe called lawmakers into special session in September at the insistence of President Donald Trump to give Republicans seven instead of six of Missouri’s eight congressional seats.

The new Missouri map targets the Kansas-City based 5th District, held by Democratic U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, to flip to the Republican Party.

Trump wants to preserve and expand the GOP’s slim majority in Congress, where they have a 219-213 edge in the U.S. House of Representatives. Democrats have countered with gerrymandering plans in states they control, with California on Nov. 5 approving a plan to deliver up to five seats to Democrats.

The Missouri Republican Party, which intervened in the case, argued that Limbaugh didn’t have the power to consider the challenge. The federal Constitution grants state legislatures exclusive power over the time, place and manner of congressional elections, Washington, D.C., attorney John Gore said, subject only to federal law.

“That means courts, including this court, do not have free reign to review and invalidate state legislative enactments on federal elections, including congressional redistricting plans,” Gore said.

At the end of Wednesday’s 45-minute trial, Limbaugh gave attorneys on both sides 10 days to file proposed judgments. No decision will be delivered until after those filings.

The case is one of six pending in various courts concerning the new map.

One case, filed by the Missouri NAACP, challenged the authority of Kehoe to call lawmakers into a special session for redistricting. Limbaugh ruled against the NAACP but an appeal is certain.

The next case to be heard will be a Thursday trial before Cole County Circuit Judge Daniel Green over an effort to force a referendum on the map. The trial, postponed from Nov. 3, will be over whether a referendum petitioning effort can begin before legislation has been signed by the governor.

A federal trail scheduled for Nov. 25 will test whether a state referendum on a redistricting plan violates the U.S. Constitution.

Two other cases, filed in Jackson County, contest various aspects of the gerrymandered map, including whether a Kansas City voting district was inadvertently placed into two separate districts.

The constitutional directive on redistricting mandates that Missouri lawmakers revise district lines after census results are delivered to the state. The provision mandates that the districts be as equal in population as possible and made up of compact, continuous territory.

The current district boundaries were set in 2022 after the 2020 census.

The provision creates an obligation to redistrict after a census and no obligation to do it at any other time, Capozzi said. But without an express prohibition, lawmakers are free to do so.

And, he added, the boundaries of congressional districts are a political question the courts should avoid.

“This court cannot wade into that political fight without an express warrant,” he said.

The case is more ordinary than Capozzi portrayed it, Hatfield said. He likened it to every other challenge to new legislation.

That means the courts must measure it against the prohibitions on legislative power, both expressly stated and interpreted. In the case of the silence on mid-decade congressional redistricting, he said, Limbaugh should look at the provisions governing how legislative districts are determined.

That provision allows districts to be “altered from time to time as public convenience may require. The omission of that language is a conscious choice made by the drafters of the constitution, he said.

“The state’s view seems to say that you need a ‘thou shalt not’ sentence in here,” Hatfield said. “That’s never been the law in Missouri.”